Stopping the toad invasion

Cane toads are really good invaders. They move astonishing distances, and they breed like maniacs. A female toad can lay thousands of eggs at a go, and while many of these won't survive, it's clear that this reproductive potential means that toad populations can grow very fast indeed.

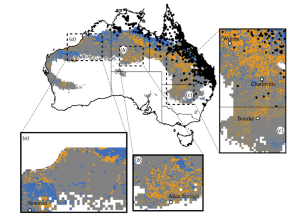

So what chance do we ever have of halting their invasion across northern Australia? A few years ago, I would have said none. But that's before I saw this map.

This map shows the distribution of artificial (orange) and natural (blue) waterpoints in northern Australia. It's from a great paper by Florance and others. In their paper they point out that artificial waterbodies (primarily put in by graziers to water cattle) increase the connectivity of the landscape for toads. They make a pretty good case that if artificial waterbodies weren't present in, say, the region between Broome and Port Hedland (section "a" in their map, above), then toads couldn't actually move through that landscape.

This seemed a pretty interesting notion, so some colleagues and I decided to put it to the test. To do this we built a simulation model that does a very good job of re-creating the observed spread rate in toads. I'll spare you all the details, but the gist is that, in the wet season (summer in N Oz), when the world is a wonderful place for toads, they get to move around and breed and do all the things that toads love to do. Come the dry season however (winter) toads have to find a waterbody, else they die.

Our simulation model utterly confirmed the notion that toads couldn't spread between Broome and Port Hedland in the absence of artificial waterbodies. Moreover, we were also able to show that you don't even really need to imagine all of these artificial waterbodies gone. There are lots of places that will work as a barrier to toad spread if you "remove" enough waterbodies. So there it is: in principle it is possible to stop the spread of toads into the Pilbara —you just need to stop them using a subset of the artificial water points that dot this corridor. The movies below show an example of spread with and without one of these waterless barriers in place.

There's a big gap between theory and practice, however. People's livelihoods depend on these water points, and, if we look hard enough, we may find other parts of the landscape that will allow toads to persist over the dry season (e.g., small springs). Darren Southwell, Reid Tingley and myself are currently engaged in closing this theory-practice gap. Can it really be done? Can we really keep toads out of 230,000 square kilometres of their potential range? Watch this space.