The evolution of virulence during range shift

All these fascinating results showing that things on expanding range edges evolve in certain ways got me thinking. When pathogens spread through novel host populations (think Ebola, currently spreading; or West Nile Virus, recently spreading) then they are in the same situation as an invasive species such as toads. That is, we should expect evolution to favour highly dispersive and rapidly reproducing variants of the pathogen on its expanding range edge.

If you're a pathogen, what does it mean to become more dispersive or have a faster reproductive rate? Well, that depends on how you are transmitted. But for simplicity, let's just say that you are a vectored pathogen — some handy creature moves you around, and that handy creature is not your primary host —like Malaria, for example. Well, in that case, I reckon there should be a strong expectation that you will evolve increased reproductive rates on an expanding range edge. If you're on that expanding range edge you are in a situation of constantly having a fresh supply of susceptible hosts. This kind of situation will tend to lead to increased virulence, because transmission is relatively easy (lots of hosts), and if you are dispersed by something else, then you can afford to make your primary host pretty darn sick. So, on balance, there's a reasonable case that a vectored pathogen might well become more virulent on its expanding range edge.

I'd been really keen on this idea for a few years, but had no data to test it with. Until I got chatting with Robert Puschendorf. Rob had been working on chytrid fungus; a pathogen that is strongly implicated in the global amphibian declines of the last forty years. Rob had collated the efforts of many researchers in Central America who had all looked at the arrival time of this pathogen and the time that the amphibian populations crashed. Each study, in isolation, was simply another example of amphibian declines happening shortly after the arrival of chytrid fungus. Together, however, these studies can tell us about the spatiotemporal dynamics of pathogen spread and population decline. It looked, for example, like chytrid had spread from north to south through central America over the last 40 years. While Rob and I talked over what could be done with these data, it slowly dawned on us that we could use them to test the idea of virulence changing during range advance.

The data were of two types. First, we had data on population numbers of monitored amphibian populations over time, which could give us, for each monitored site, a rough idea about when the population crashed. Second, for each of these sites there were also data on chytrid prevalence over time, which could be used to give us a rough idea of when chytrid arrived. I say rough because in many cases it was pretty rough —samples might be more than five years apart, for example, so we might have, for a particular site, a five year window in which things could have happened. For some sites the window was more like 20 years!

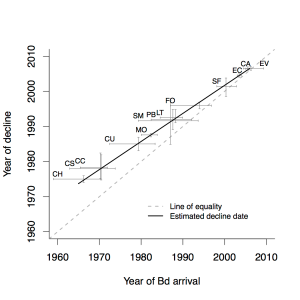

These are the realities of ecological data — they're often messy — but at least we had a simple hypothesis. If chytrid virulence had remained unchanged, then the lag time between chytrid arrival and population decline should be constant over time. If we look across all 13 sites for which we had data, this should manifest as a relationship between decline date and arrival date that has a slope of one.

It was good we had a simple hypothesis, because the analysis was quite difficult. But to cut a long story short, we ended up with a very clear result that the slope of the relationship between dates of decline and arrival were less than one. In other words, as time went on (and the chytrid invasion spread south) the lag between its arrival and amphibian decline became smaller and smaller. This wasn't a small effect: when chytrid first arrived on the scene in the mid 70s it was taking 5-7 years to impact amphibian populations. By the time it had spread all the way through central America, the lag time was closer to six months. It certainly looks like chytrid became a lot more virulent as time (and spread) went on. We published this result here.

So is this support for the notion of evolving virulence during spread? Well, maybe. While it's a pretty compelling case that chytrid became more virulent as it spread, we can't rule out some environmental factor (e.g., latitude, climate change) that facilitated this pathogen, making it more virulent. To be sure that the pattern was driven by evolution It'd be great if we could dig up some old preserved chytrid strains and test them against the "newer" ones. It's a bit outside my expertise, but I really hope someone does this one day.

Finally, after the paper was published, Alex Perkins very politely pointed out that he'd noticed the exact same possibility — evolution of virulence during pathogen spread — as an outcome of some of his (really excellent) modelling work. And I'd failed to a) realise this, and b) cite his work. So while I get to feel bad that I didn't include his work in our paper (sorry again, Alex), I also get to feel good that a very good theoretician independently came up with the same idea.