Evolution on the edge: a model system for evolution on invasion fronts

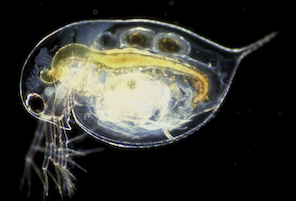

This project aimed to develop a shared experimental platform, using the well-studied ecological model, Daphnia, to test emergent predictions about evolution on invasion fronts. Evolution happens rapidly on invasion fronts, accelerating the speed and potentially the damage caused by an invasion. By manipulating invasions through an experimental landscape, the project aimed to answer currently infeasible questions, including whether pathogens become more virulent as they spread, and whether evolutionary trade-offs place limits on spread rate. The findings may have implications for the management of phenomena ranging from emergent diseases to invasive pests and malignant growths.

Progress

One of the big ideas here was to develop a native Daphnia species as a model for Australian researchers to work on questions in spatial ecology and evolution. And to answer some cool questions about invasive pathogens along the way. It turned out to be a tricky project. Despite serious effort from PhD student Sally Drapes, we didn’t manage to find a pathogen, so a big part of her project got re-designed. Daphnia carinata also proved to be very tricky about how they would disperse through the spatial arrays we built. Initial trials worked beautifully in a particular setup — the Daphnia dispersed nicely between our experimental patches — so we went big on this setup. As soon as Phil Erm had built the 300-patch array, however, the Daphnia stopped dispersing through them, and it proved very difficult to work out why. The project became an exercise in perseverance and creative adjustment.

Nonetheless, we finally managed to use the system (and the classic system using a northern hemisphere Daphnia) to address fundamental questions around the ecology and evolution of invasive populations. We show that spreading pathogens are under fundamentally different evolutionary pressures than endemic pathogens; that pathogens specialise functions across host sexes (using males for dispersal, and females for reproduction); and that host dispersal depends on local conditions. We also uncovered a dizzying complex of plastic and genetic life history variation in Australian Daphnia. The project also developed important new theory addressing the nature of natural selection, and evolution on invasion fronts.

The project supported two PhD students (Sally Drapes, Louise Noergard), two Masters students (Phil Erm, Kim Chhen), and two undergraduate students (Erin Campbell-Hooper, and Tahlia Townsend), as well as several other PhDs that were more peripherally involved.

Selected publications

Drapes, Sally, Matthew D. Hall, and Ben L. Phillips. (2021) Effect of Habitat Permanence on Life-History: Extending the Daphnia Model into New Climate Spaces. Evolutionary Ecology 35: 595–607.

Nørgaard, Louise. Solveig, Ghedini, Giulia, Phillips, Ben. L., Hall, Matthew. D. (2021). Energetic scaling across different host densities and its consequences for pathogen proliferation Functional Ecology. 35: 475–484.

Erm, Philip, Phillips, Ben. L (2020). Evolution transforms pushed waves into pulled waves The American Naturalist. 195: E87–E99.

Phillips, B. L, Perkins, T.. Alex (2019). Spatial sorting as the spatial analogue of natural selection Theoretical Ecology. 12: 155–163.

Nørgaard, Louise. S., Phillips, Ben. L., Hall, Matthew. D. (2019). Infection in patchy populations: Contrasting pathogen invasion success and dispersal at varying times since host colonization Evolution Letters. 3: .

Nørgaard Louise Solveig, , Phillips Ben L., , Hall Matthew D., (2019). Can pathogens optimize both transmission and dispersal by exploiting sexual dimorphism in their hosts? Biology Letters. 15: 20190180.

Erm, P. E, Hall, M. D, Phillips, B. L (2019). Anywhere but here: local conditions alone drive dispersal in Daphnia PeerJ. 7: e6599.