Evolution makes invasions unpredictable

Pop quiz: what have cancer and cane toads got in common? Well, as it turns out, quite a lot. They're both examples of a spreading population. In the case of toads its a population of... well, toads. In the case of cancer, it's a population of cells. But in both cases, the population spreads by movement and reproduction of its 'individuals'. Indeed, when you stop to think of it, spreading populations are everywhere.

The other thing that toads and tumours have in common is that their spread rate is difficult to predict. This unpredictability is frustrating, for a couple of reasons. First, for lots of spreading populations, we'd really (really) like to predict spread rate. It would be nice to know how rapidly that tumour is likely to grow, or that invasive species is going to spread. Second, it is frustrating because we actually have some really beautiful theory about population spread to guide us. The fact that this theory often fails badly in the forecasting stakes is, to put it mildly, deeply irritating.

Why is the spread rate of invasive populations so darn tricky to nail down? Part of the reason is that the processes driving spread -- dispersal and reproduction -- always contain random variation. For reasons we can't anticipate, some individuals move further than others, or leave more offspring behind than others. As well as this, and again, for reasons we can't anticipate, some moments in time are better for spread than others. In the case of toads, for example, one individual might move 15kms and leave 10,000 babies behind. Another individual from the same clutch might be run over by a truck. If they'd started at a different moment in time, they might both have moved about 10km and left about 10,000 babies behind. These inherently unpredictable events make it tricky to predict spread rate, but they're not the worst of it, not by half. I've recently come to the conclusion that the main reason that invasions are unpredictable is because of evolution.

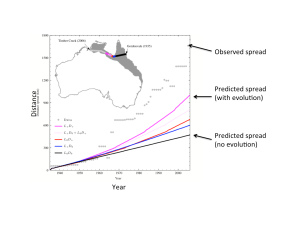

We've established (in earlier posts) that evolutionary forces on the invasion front are utterly different to those behind the invasion front. To cut to the chase: on the invasion front, evolution favours higher rates of dispersal, higher rates of reproduction, and (to pay for these) lowered competitive ability. These evolutionary shifts cause population spread to accelerate over time. So one reason why earlier theory tended to underestimate actual spread rates is because this earlier theory failed to take into account evolution. This idea was neatly demonstrated recently with a model dreamt up and executed by Alex Perkins. By examining the spread of toads, Alex was able to show that a standard (non-evolutionary) model predicted that toads should have spread about 400km from Cairns in 75 years. In fact, they spread well over 1800km; an outcome that an evolutionary model did a much better job of predicting. So here's one reason why evolution matters (a lot) if you're trying to predict spread rate.

Alex's work was really cool, but one of the frustrations for me was noting that even his evolutionary model fell well short of the actual spread rate of toads. What's with that? At the time, we argued that spread rate is tricky and that the random processes I've talked about above probably explain the discrepancy. Well, maybe.

Another really important thing to remember about invasion fronts is that they are made up of very few individuals, and they move. In practice, this means that, of the massive population of cells/toads/whatever, only a very few make up the invasion front each generation. While these few will tend to be good dispersers, and have high reproductive rate, there's also a big element of chance. When you flip a coin 100 times, there's an almost 100% chance that you'll get at least one head. When you flip it once, you've only got a 50% chance of seeing a head. So it goes with invasion fronts. Let's imagine there's a 60% chance of seeing a good disperser. If the invasion front was made up of 100 individuals, it's almost certain you would see a good disperser on the front. If the invasion front is made up of only a single individual... well, there's now a 40% chance that you don't get a good disperser. The numbers are made up, but you get the point: even though evolution favours good dispersers, there's a chance they won't turn up on the invasion front.

In the parlance of evolutionary biologists, genetic drift -- a measure of randomness in evolution -- is strong on the invasion front. In fact, on invasion fronts, the strength of this genetic drift is so high that it can lead to populations evolving in ways that are clearly bad for the population. Populations can evolve to be less fit over time on invasion fronts.

Let's stop and digest all that for a second. Evolutionary forces on the invasion front push populations towards increased dispersal and reproductive rates. But that pushing force is being disrupted by the random process of drift. When a leaf falls from a tree, the force of gravity pushes it straight down. Where it actually lands, however, is influenced by many random processes. Although we can predict that dispersal and reproductive rates should increase on the invasion front, it is almost impossible to predict how quickly and by how much. So the traits that determine spread rate -- dispersal and reproduction -- evolve, but they do so in an unpredictable fashion. As a consequence, spread rates typically increase over time, but in an unpredictable fashion.

If we want to predict the spread rate of toads, tumours, or trees, we clearly need to take account of evolution. Unfortunately, doing so leads us to a new problem: evolution on the invasion front is, itself, likely to be highly unpredictable. Damn.

Where does this leave us? First, it's important to point out that I could be wrong about all this. I'll be much happier about these ideas when some hard-core theoreticians go over them. I've had a crack at modelling these ideas, but others are better at these kind of things than I. Let's assume, for now, I'm right. Well, in that case, I'd argue that for many spreading populations, evolutionary processes place fundamental limits on our ability to predict that spread. This is not to say that we shouldn't attempt to predict spread rate: we should, but we should also be clear about our uncertainty in that prediction. Evolutionary processes mean that we are much more uncertain than we previously thought. It seems we have been way too confident in our estimates of spread rate, and so we've been consistently surprised when reality confounds our predictions. At least we now know why.